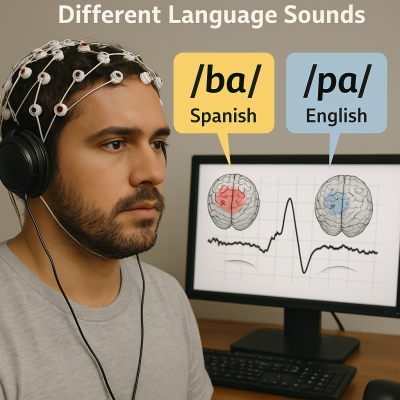

In both English and Spanish, speech sounds like “b” and “p” differ in a feature called voice onset time, or VOT. That is just a fancy way of saying how much time passes between when your lips make a sound and your vocal cords start vibrating. Spanish “b” sounds often start vibrating before the sound is released (prevoicing), while English “b” sounds start vibrating right at the release. The brain needs to figure out whether a given sound belongs to the English or Spanish system.

In both English and Spanish, speech sounds like “b” and “p” differ in a feature called voice onset time, or VOT. That is just a fancy way of saying how much time passes between when your lips make a sound and your vocal cords start vibrating. Spanish “b” sounds often start vibrating before the sound is released (prevoicing), while English “b” sounds start vibrating right at the release. The brain needs to figure out whether a given sound belongs to the English or Spanish system.