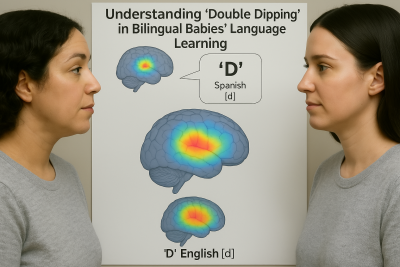

When babies hear the same sound in two languages—like the letter D, which is pronounced a bit differently in English and Spanish—their brains have to figure out which version belongs to which language. English speakers tend to pronounce the D quickly and without voicing beforehand, while Spanish speakers often add a short buzz (called pre-voicing) before saying the D.

When babies hear the same sound in two languages—like the letter D, which is pronounced a bit differently in English and Spanish—their brains have to figure out which version belongs to which language. English speakers tend to pronounce the D quickly and without voicing beforehand, while Spanish speakers often add a short buzz (called pre-voicing) before saying the D.